by Peter Salonius, a Canadian soil microbiologist

by Peter Salonius, a Canadian soil microbiologist

[the original, lengthy article can be seen here. This is a crucial topic, covered in some depth by the article - ed.]

Part 1: Life Before Agriculture

The major departure for humans as just another member of the global animal species assemblage came when fire was first used about 400,000 years ago by Homo erectus (Price 1995). The dynamic cyclical stability of complex systems has been shown for most animal populations, except top predators, to depend on predation to dampen overshoot and runaway consumption dynamics of prey species (Rooney et al. 2006). The ability to control and use fire removed the influence of wild animal predators as moderators of human numbers. The use of fire made possible the colonization of cold lands at high latitudes where fuel for heating shelters was available in some form such as animal oil, dried dung and wood. Even though their shelters became more complex and elaborate, they were, for the most part, temporary encampments whose main structural components could be transported across the landscape so as to benefit from variable food availability as the seasons changed.

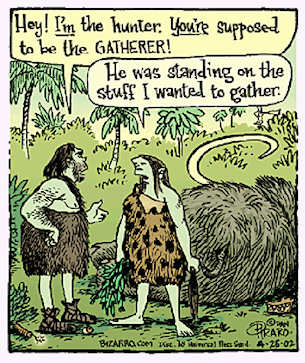

The bulk of human history has been that of a culture of hunter gathers or foragers. They did not plant crops or modify ecosystem dynamics in any significant manner as they were passively dependent on what the local environment had to offer. They did however domesticate dogs as early as 100,000 BCE (Vila et al. 1997); these animals were useful as hunting aids, guardians, and occasionally as food during times of scarcity. Hunter gatherers maintained social organization and interdependence, and prevented the loss of food to spoilage by sharing the harvest among community members. These people lived in harmony with their supporting ecosystems and their ability to unsustainably stress and damage their environment was limited by the fact that if their numbers exceeded the carrying capacity of the complex, self-managing, species diverse, resilient terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems from which they gained their sustenance, then hunger and lower fertility exercised negative feedback controls on further expansion.

They used culturally mediated behavior like extended suckling, abortifacients and infanticide to keep their numbers far below carrying capacity, and to avoid Malthusian constraints like starvation (Read and LeBlanc 2003). Warfare between groups competing for the same resources, before the evolution of states, also appears have been a significant constraint on the growth of human numbers (Keeley 1996).

Part 2: The Evolution of Agriculture

The development of agriculture is of great interest to us because it produces most of our food and it was a prerequisite for the tremendous growth of human numbers, and also for the various complex societies that have evolved since this new culture began (Diamond 2002).

After the advent of agriculture, mortality rates, caused by conflict, decreased somewhat as local raiding by chiefdoms evolved into long-distance territorial conquest by states (Spencer 2003). These cultural and conflict behaviors that limited human population growth served to maintain balance between humans and other species during most of the historical record. Read and Leblanc (2003) suggest that humans, in areas of low resource density, tend to maintain generally stable populations, while high resource density, such as that produced by agriculture, decreases the spacing of births more rapidly than the increase in resource density, which results in repeating cycles of carrying capacity overshoot and population collapse.