If climate disasters are to be averted, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) must be reduced below the levels that already exist today, according to a study published in Open Atmospheric Science Journal by a group of 10 scientists from the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

If climate disasters are to be averted, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) must be reduced below the levels that already exist today, according to a study published in Open Atmospheric Science Journal by a group of 10 scientists from the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

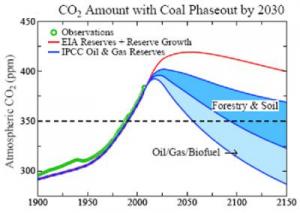

The authors, who include two Yale scientists, assert that to maintain a planet similar to that on which civilization developed, an optimum CO2 level would be less than 350 ppm — a dramatic change from most previous studies, which suggested a danger level for CO2 is likely to be 450 ppm or higher. Atmospheric CO2 is currently 385 parts per million (ppm) and is increasing by about 2 ppm each year from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas) and from the burning of forests.

"This work and other recent publications suggest that we have reached CO2 levels that compromise the stability of the polar ice sheets," said author Mark Pagani, Yale professor of geology and geophysics. "How fast ice sheets and sea level will respond are still poorly understood, but given the potential size of the disaster, I think it's best not to learn this lesson firsthand."

The statement is based on improved data on the Earth's climate history and ongoing observations of change, especially in the polar regions. The authors use evidence of how the Earth responded to past changes of CO2 along with more recent patterns of climate changes to show that atmospheric CO2 has already entered a danger zone.

According to the study, coal is the largest source of atmospheric CO2 and the one that would be most practical to eliminate. Oil resources already may be about half depleted, depending upon the magnitude of undiscovered reserves, and it is still not practical to capture CO2 emerging from vehicle tailpipes, the way it can be with coal-burning facilities, note the scientists. Coal, on the other hand, has larger reserves, and the authors conclude that "the only realistic way to sharply curtail CO2 emissions is phase out coal use except where CO2 is captured and sequestered."

In their model, with coal emissions phased out between 2010 and 2030, atmospheric CO2 would peak at 400-425 ppm and then slowly decline. The authors maintain that the peak CO2 level reached would depend on the accuracy of oil and gas reserve estimates and whether the most difficult to extract oil and gas is left in the ground.

The authors suggest that reforestation of degraded land and improved agricultural practices that retain soil carbon could lower atmospheric CO2 by as much as 50 ppm. They also dismiss the notion of "geo-engineering" solutions, noting that the price of artificially removing 50 ppm of CO2 from the air would be about $20 trillion.

While they note the task of moving toward an era beyond fossil fuels is Herculean, the authors conclude that it is feasible when compared with the efforts that went into World War II and that "the greatest danger is continued ignorance and denial, which could make tragic consequences unavoidable."

"There is a bright side to this conclusion" said lead author James Hansen of Columbia University, "Following a path that leads to a lower CO2 amount, we can alleviate a number of problems that had begun to seem inevitable, such as increased storm intensities, expanded desertification, loss of coral reefs, and loss of mountain glaciers that supply fresh water to hundreds of millions of people."

In addition to Hansen and Pagani, authors of the paper are Robert Berner from Yale University; Makiko Sato and Pushker Kharecha from the NASA/Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Columbia University Earth Institute; David Beerling from the University of Sheffield, UK; Valerie Masson-Delmotte from CEA-CNRS-Universite de Versaille, France Maureen Raymo from Boston University; Dana Royer from Wesleyan University and James C. Zachos from the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Citation: Open Atmospheric Science Journal, Volume 2, 217-231 (2008)