One of my very favourite quotes about population and ecology comes from an unnamed friend on the Internet:

One of my very favourite quotes about population and ecology comes from an unnamed friend on the Internet:

Asking ,"How will we get enough food to feed this growing population?" is a lot like asking "How will we get enough wood to feed this growing bonfire?"

The point of the quote is that most people have the ecological cause and effect of food and population exactly backwards. The real problem is not that a rising population requires more food, but that an increasing food supply drives populations ever upward.

While this makes for a nice pithy quote, and is a useful idea on its own, the real situation is, as always, more complex than that. I've recently been thinking about this idea, trying to fit it into a more comprehensive view of population growth that takes into account both human and non-human species. Unfortunately, in the process I've beaten the pith out of the original quote...

Food supply is, of course, one of several factors that combine to limit the population of any species. If the food supply is capped that naturally places a hard upper bound on the population. Other limiting factors seem to be predation, disease and behavioural changes (whether voluntary or instinctual). There may be others, but those look like the biggies. Environmental breakdown usually limits populations by affecting either the food supply or disease rates, so it's only a proximate cause of population decline.

So populations have their own version of "Liebig's Law of the Minimum": if one factor proves limiting to population growth, it doesn't matter how permissive the other factors are.

Consider a classic predator/prey dynamic, such as foxes and rabbits. As the fox population grows and predation increases then the rabbit population declines, no matter how much food is available to the rabbits. Then as the rabbit population declines the fox population stops growing due to the lack of food. Simple stuff. Of course humans have no predators, so predation not a Liebig Minimum for us.

If a lethal disease infects a population, it doesn't matter how much food there is, the disease establishes the limit. We humans have population-level disease under control, so that's not a limit for us either.

By the way, some people think war could limit our population, but I seriously doubt that. A war, even a thermonuclear war, is just not big enough to permanently reverse our population trend. A war with a billion casualties (over ten times the size of World War II) would set our population back less than 15 years, though it might take longer than that to recover the loss.

Thinking strictly of the human situation: our food supply is not capped at the moment; we have no predators; and we have no large disease problem. The only thing mitigating our population growth right now is fertility reduction due to behavioural change, whether it's through women's education, Virginia Abernethy's proposed fertility-opportunity mechanism, or the effects of increasing wealth proposed by the Demographic Transition Model. Behaviour changes are bringing down our overall birth rate, but not yet fast enough to keep our total population from growing.

It's axiomatic that our population will keep growing until the global net birth rate drops to 0. The UN says that may happen within 40 years, at a population of 9 to 10 billion in 2050. I'd call that a "soft limit", as it doesn't require an increase in the death rate, just a reduction in our birth rate.

A "hard limit" would be a factor that increases our death rates or lowers our average life expectancy. Predation is not ever going to be a problem for humans, so the main candidates for possible "hard limits" are diseases and food supplies.

Disease could become a limiting factor if we have a major pandemic, but it would have to be awfully big – even major diseases like the Black Death and the Spanish Flu haven't stopped us before. It is possible for serious disease to get a foothold in our population, though. We could, for example, experience a dramatic rise in a variety of lethal diseases if the social infrastructure that supports our medical system crashes. Collapses of urban sanitation systems in major cities could also do it, allowing the spread of cholera, dysentery and typhoid. However, we now know enough about the origins of disease to protect ourselves pretty well. Given our recent record with potential pandemics, I'd say the probability of the world population being decimated by a disease (or even several) seems low.

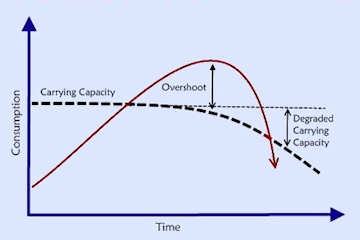

So that leaves the food supply as the primary threat. We are already in overshoot, and overshoot always brings down the food supply over the long term. The signs are ominous – declining ocean fish stocks, dropping soil fertility, losses of arable land and fresh water, rising fertilizer prices, hints of trouble in the constrained genomes of various food sources, etc.

If our food supply is the major risk that humanity faces over the next 50 to 100 years, then we have to acknowledge a serious question. Can we alter our food production practices enough by 2050 or so to establish an equilibrium between a behaviourally stabilized human population of 10 billion or so (given that it does in fact stabilize there) and the long-term productivity of the biosphere, all in the presence of climate change and the inevitable shift in our energy infrastructure as we are forced to move away from fossil fuels.

Many very clever people are working on various aspects of this problem: the permaculturists, the locavores, Big Agribusiness (God help us), scientists of all sorts, some city planners, anthropologists and even Bill Gates.

Will we win the race? How clever are we really? And how wise? I suspect we're going to find out fairly soon.